This year, the vernal equinox falls on 20 March. However, in practice it has been spring for a long time, at least in central and southern Sweden. In Skåne, there was no actual meteorological winter and spring arrived unusually early, resulting in blooming daffodils and Japanese cherry trees.

Clear trend

An uncommonly early spring or mild winter alone cannot be seen as an indication of climate change. However, the trend is clear – Sweden’s climate has become increasingly warm, which is in line with global warming, says Markku Rummukainen, professor of Climatology at Lund University. On an annual basis there has been a temperature increase of about two degrees in recent decades.

“This warming affects all the seasons and means that we will have milder winters and earlier springs more often. Then, of course, there is always a variation between the years”, he says.

How, then, is nature responding to an increasingly warm climate? According to a new study from Lund University in Sweden, there has been a clear effect on vegetation.

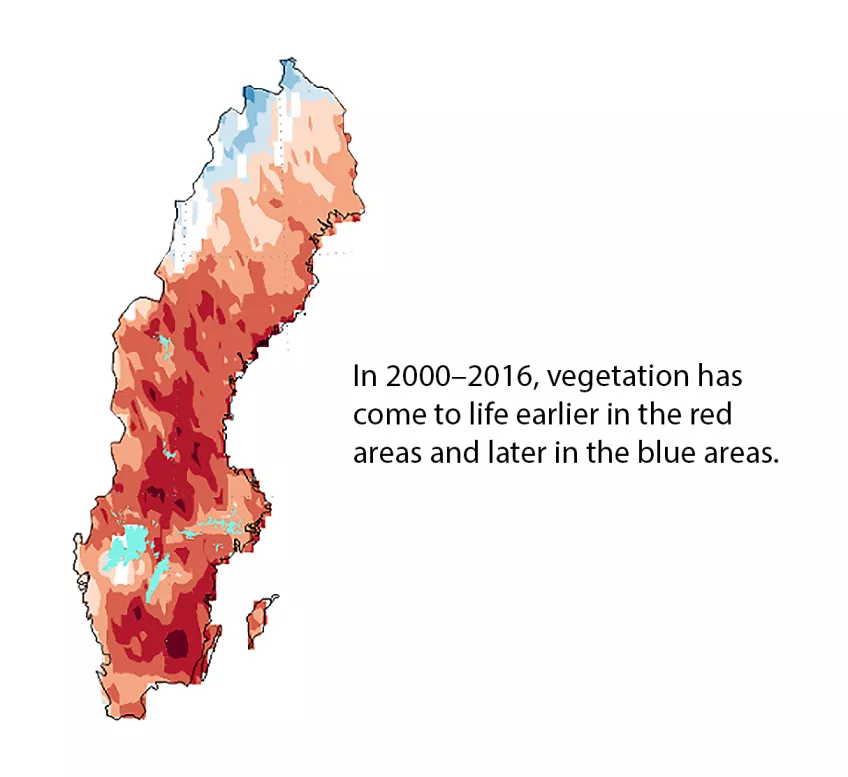

“What we are seeing, using satellite data, is that vegetation arrives earlier and earlier each year”, says Lars Eklundh, professor at the Department of Physical Geography and Ecosystem Science.

Unsynchronised nature

The researchers examined a 16-year period. The results show that in 2016 greenery arrived 8 to 16 days earlier than in 2000 in large parts of Sweden. On average, this means that in northern Europe, the vegetation comes to life 0.3 days earlier per year, or a half to full day earlier per year in the areas of Sweden where the change is happening most rapidly. According to Lars Eklundh, the cause is warmer temperatures. The effect is a shorter winter and thus a longer growing season, which means, among other things, that trees will grow faster.

Lars Eklundh cannot say what the long-term consequences may be of vegetation coming to life earlier in the spring, but he fears that nature will become unsynchronised and the phenology – the date each year when a certain phenomenon happens in nature – will be disrupted.

“Personally, I feel some concern. It’s a rapid change and nature is not really prepared for it. All organisms will have to keep up with this change”, he says.

Another clear effect of a warmer climate is that, on average, migratory birds now return to Sweden up to ten days earlier compared with 30 to 40 years ago.

“Birds are a very good barometer regarding how the climate affects nature”, says Åke Lindström, professor of Biology at Lund University and head of Swedish bird monitoring.

“Higher temperatures also mean that species which are normally further south on the continent and thrive in a warmer climate will gradually increase in Sweden. In a corresponding way, birds that thrive in a colder climate will decline and be drawn further north”, says Åke Lindström.

On the positive side, bird species rarely crowd each other out. Åke Lindström therefore sees no risk that new species will become established in Sweden.

New competitors för certain species

The situation is different regarding plants. Here again, certain species are increasing while others are declining. Above all, there is an increase in evergreen bushes and other plants that previously would not have survived the winters in Sweden because the leaves or stems froze. However, the consequences of warmer temperatures don’t end there, emphasises Torbjörn Tyler, associate professor of Biology and curator of the Botanical Museum in Lund.

“It’s not that simple. One effect of this may be that species get out of sync with each other. This makes everything more unpredictable than it would be otherwise”, he says, and mentions, for example, that species may find they have new competitors.

Regarding pollinators, there is a lack of sufficiently good time series, but the researchers have managed to piece together a picture of the situation, comments Johan Ekroos, researcher at CEC. He also warns of the problem of nature being out of step.

“A gap may arise between flowers blooming and the arrival of the pollinators. If, for example, this is due to a major heatwave, the blooming will peak early and then crash, and that could have dire consequences for the pollinators”, he says.

The article about spring phenology in International Journal of Biometeorology (PDF, 3 MB, new tab)